Crash Course on Time Domain (DELAY) Effects.

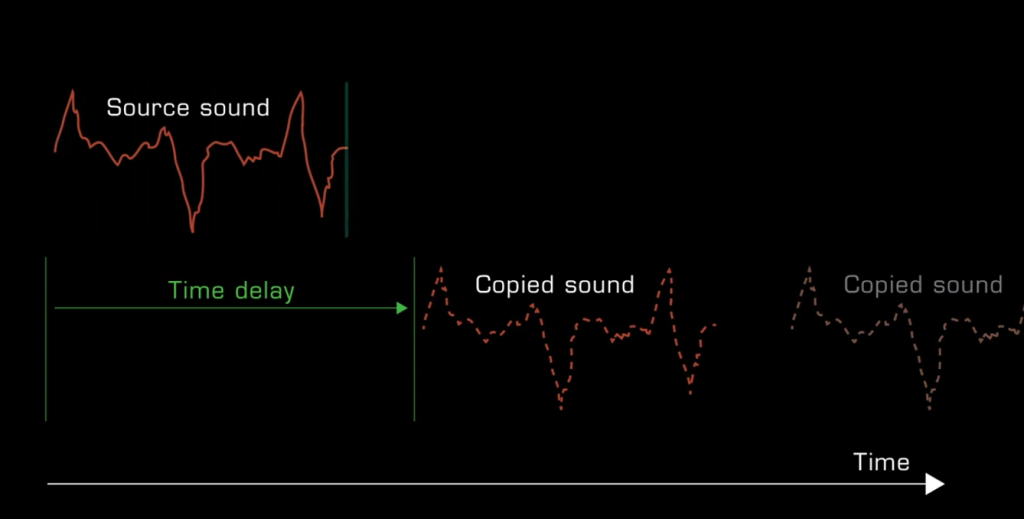

Time domain effects are created by making single or multiple copies of a source sound, delaying those copies in time, and then mixing the delayed signals back with the original. This simple principle forms the foundation of a wide range of audio effects that are central to modern sound production.

At their core, time domain effects manipulate when a sound is heard rather than what the sound is. By controlling timing relationships between the original signal and its copies, these processes create movement, depth, width, and repetition within an audio signal.

Time domain effects are defined by delay, duplication, and the interaction between original and delayed sound.

Primary Time Domain Effects

Several widely used effects are classified as time domain effects due to their reliance on delayed copies of audio. These include:

- Phasing

- Flanging

- Chorus

- Automatic Double Tracking

- Slapback Echo

- Conventional Delay

Each of these effects is based on the same underlying mechanism: a delay line. What differentiates them is the delay time, number of copies, modulation, and mix balance between the original and delayed signals.

Although they may sound complex or distinct, all of these effects can be created using variations of a simple delay line.

Understanding the Delay Line

The term “delay line” describes any process in which a source sound is copied and delayed in time. The delay can be extremely short—measured in milliseconds—or long enough to create clearly audible repeats.

A delay line does not inherently define the sound of an effect. Instead, it provides the basic mechanism that allows time-based manipulation. The character of the effect emerges from how the delay line is implemented and controlled.

A delay line is not an effect by itself—it is the engine behind time-based effects.

Technologies and Techniques for Creating Delay

Delay lines can be implemented using a variety of technologies, both historical and modern. These approaches differ in sound character, precision, and flexibility.

Tape Delay

Tape delay utilizes the physical distance between the record head and the repro (playback) head of a tape recorder. As the tape moves, the recorded signal is replayed after a short time gap.

Key characteristics of tape delay include:

- Natural saturation

- Slight pitch instability

- Gradual high-frequency loss over repeats

Solid-State Analog Delay

Solid-state analog delay processors, such as pre-digital guitar delay pedals, use analog circuitry to store and delay audio signals. These devices often impart a distinct tonal coloration.

Common traits include:

- Darkening of repeated signals

- Limited maximum delay times

- Smooth, musical degradation

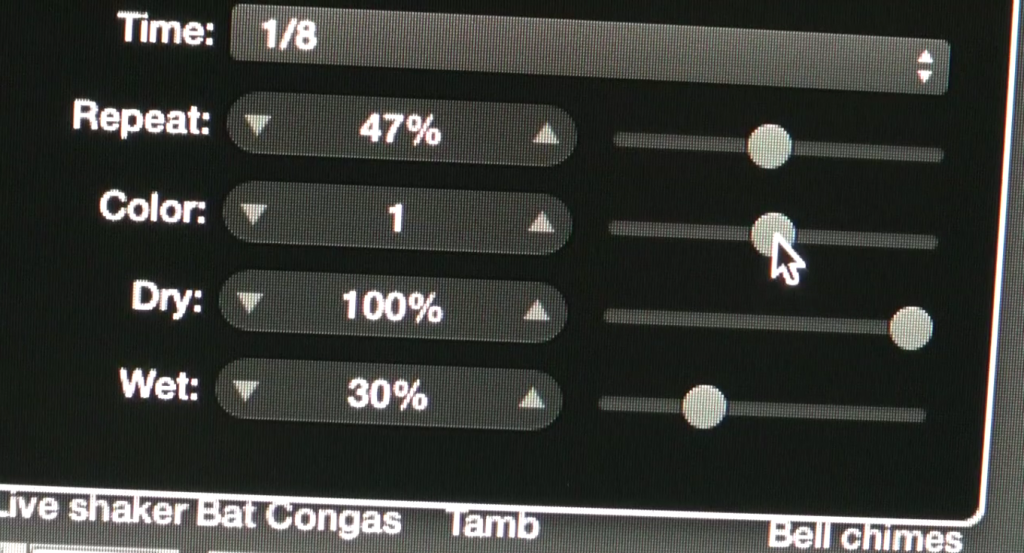

Digital Delay Processors

Digital delay processors store audio digitally, allowing for:

- Highly accurate repeats

- Long delay times

- Precise control over feedback and timing

Digital delays can repeat a signal endlessly if required, producing near-identical duplicates of the source sound.

Software-Based Delay

Modern production environments commonly use:

- Digital delay plugins

- Tape echo emulations

- Track duplication with manual delay offsets

Duplicating an audio track and delaying the duplicate provides a straightforward method for creating time-based effects directly within a digital audio workstation.

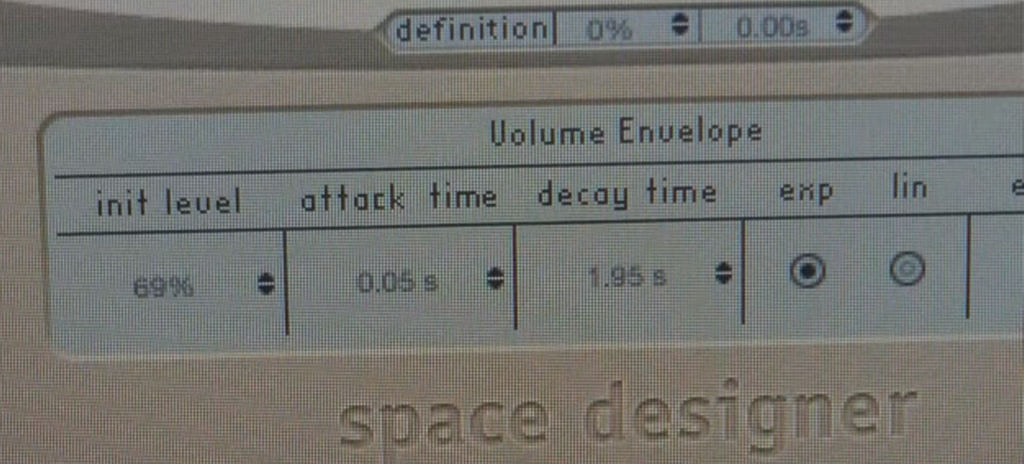

Reverberation as a Time Domain Effect

Reverberation is also classified as a time domain effect, but it occupies a unique position due to its complexity.

Unlike other time domain effects, reverberation cannot easily be created with only a few delayed copies. Instead, it typically requires hundreds or even thousands of echoes to simulate the dense reflection patterns found in real acoustic spaces.

For this reason, reverberation is generally considered a separate category of effect, even though it shares foundational principles with echo and delay.

Reverberation is time-based, but its scale and complexity set it apart.

Echo, Delay, and Reverberation: Shared Properties and Differences

Echo, delay, and reverberation share common properties, yet they differ subtly in definition and perception.

Echo

Echo is often defined as individually distinct repeats that are clearly separated from the original sound.

Key defining characteristics include:

- A separation gap of at least 50 to 70 milliseconds

- Audibly discrete repetitions

- Natural occurrence in real-world environments

Echoes were first simulated electronically in studio environments using tape recorders, where delayed playback mimicked the behavior of sound reflecting off distant surfaces.

In studio terminology, “echo” refers to a delay line designed to replicate the natural behavior of echoes, including how sound evolves over time.

One important aspect of echo behavior is frequency decay:

- High harmonic frequencies decay faster

- Low frequencies persist longer

This frequency-dependent decay contributes significantly to the perceived realism of echo effects.

Reverberation

Reverberation is the combined effect of multiple individual echo reflections occurring in rapid succession.

Typical characteristics include:

- Initial reflections separated by less than 50 milliseconds

- Dense layering of reflections

- A smooth, continuous decay rather than discrete repeats

Although early reflections are often closely spaced, this is not always the case. The complexity of reverberation patterns depends on the size, shape, and surface materials of the space being simulated.

Delay

“Delay” is a generic technological term that refers to the creation of repeats through electronic or digital processes.

A digital delay line can:

- Sample a source sound

- Repeat it with high accuracy

- Continue repeating indefinitely if feedback is applied

Unlike echo, which implies natural behavior and tonal change, delay can produce almost exact duplicates of the source sound with minimal degradation.

“Delay” describes the process; “echo” and “reverberation” describe perceptual outcomes.

The Role of Time Domain Effects in Sound Design

Time domain effects are foundational tools for shaping spatial perception and rhythmic interest in audio. By controlling timing relationships, they influence how sound interacts with space, movement, and texture.

Whether implemented through physical tape machines, analog circuitry, or digital algorithms, the underlying concept remains consistent:

- Copy the sound

- Delay it in time

- Blend it back with the original

This simple structure supports a wide spectrum of sonic results, from subtle thickening and width to dramatic repetition and spatial depth.

Key Concepts at a Glance

- Time domain effects manipulate timing, not pitch or tone

- Delay lines are the core mechanism

- Phasing, flanging, chorus, and echo all rely on delayed copies

- Reverberation requires dense, complex reflection patterns

- Echo and delay are closely related but perceptually distinct

By understanding how delay lines function and how timing shapes perception, time domain effects can be approached as structured, predictable processes rather than abstract sonic phenomena.