Various Types of Reverb: Categories, Uses, and Real-World Context

Today, I want to share some thoughts I’ve been having about reverb—specifically how I tend to think about it when making decisions in a mix.

What I’ve done is divide reverbs into six categories—technically five plus a bonus category. These aren’t rigid definitions or technical classifications. They’re simply a way of organizing ideas to help answer one core question:

When do I like to use a plate? When do I like to use a spring? When do I like to use a room?

This approach isn’t about convolution versus algorithmic reverbs, impulse responses, plugins, or hardware. It’s about why a certain type of reverb works in a given situation—not how to set it up.

The categories are:

- Halls

- Rooms

- Plates

- Chambers

- Springs

- Nonlinear (bonus category)

You can absolutely make up your own way of thinking about reverbs. These are just the mental buckets I tend to use when deciding what direction to go in.

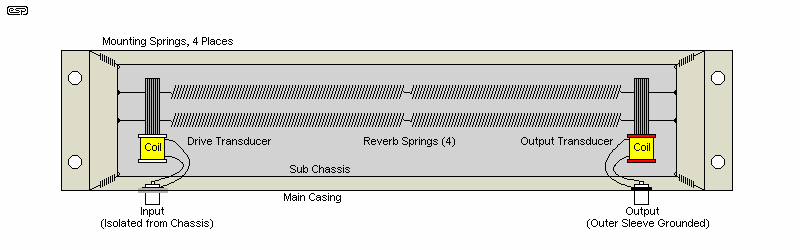

Spring Reverbs: Character, Vibe, and Controlled Space

I tend to like spring reverbs on guitars and for vintage-style vocal sounds. Think about classic, slightly retro vocal textures—the kind of vibe you might associate with older soul records or certain modern productions intentionally leaning that way.

Spring reverbs also tend to work well in mono, which reinforces that retro feel.

Where I don’t usually like spring reverbs is on drums and percussive elements. That doesn’t mean I never use them there—but it’s more of a special-effect decision. Occasionally, I’ll use a spring just to get that little “boingy” character on something like a clave.

Why springs work the way they do

Spring reverbs have a way of doing reverb things without some of the common downsides of more traditional reverbs. They can add space and movement without pushing a sound too far back.

This becomes especially important with vocals—particularly rap vocals.

The most important thing in a rap song is the rap.

And the most important thing about the rap is intelligibility, timing, and feel.

Rap vocals need to stay up close—in your face. When you add too much traditional reverb, you risk compromising clarity and timing. A spring reverb can create ambience while preserving intelligibility.

In practice, spring reverbs tend to:

- Tail off quickly

- Avoid excessive density

- Maintain vocal presence

- Add vibe without pushing the vocal backward

This makes them a strong option when you want the effect of reverb without the negative side effects.

Plates: Density, Clarity, and Vocal Focus

When I think of plate reverbs, I immediately think of vocals.

Plates aren’t generated by copying a real acoustic space. Because of that, they tend to build density quickly. You get to the “good part” of the reverb sound faster compared to many other types.

That quality makes plates particularly effective when you want a vocal to sound rich and present without feeling distant.

Key characteristics of plates

- Fast-building density

- Smooth, even decay

- Bright, controlled character

- Strong presence in a mix

With plates, I often find that using a pre-delay becomes important. It helps maintain articulation while still benefiting from the plate’s density. That said, this discussion is about why, not how.

When comparing a plate to a hall on the same vocal, the plate often feels:

- Brighter

- More immediate

- Less spatially diffuse

- Better integrated into the mix without excess depth

Hall Reverbs: Versatility and Emotional Space

Hall reverbs are probably the most versatile category.

You can change parameters and morph them into other things fairly easily, which makes them useful in a wide range of contexts. That said, I tend to gravitate toward halls in more open, emotional arrangements.

I especially like halls on:

- Ballad-style vocals

- Strings

- Classic analog-style instruments

When there’s a lot of space in the arrangement—when the music needs to breathe—hall reverbs help create that sense of depth and continuity.

They help everything feel like it’s living in the same environment.

On vocals with a classic sound, a hall can help the voice sit naturally with the rest of the instruments, especially when those instruments already share a cohesive acoustic space.

Chamber Reverbs: Bringing Synthetic Sources into the Real World

I tend to like chamber reverbs on:

- Drums

- Various instruments

- Sometimes vocals

They’re particularly useful for sounds that weren’t recorded through a microphone—for example, signals coming straight out of a synthesizer.

If I want those sounds to feel like they were captured in a live space, a chamber is often my first choice.

Chambers help bridge the gap between:

- Direct, synthetic sources

- Organic, acoustic environments

They add realism without overwhelming the source, making them a practical choice when blending electronic and acoustic elements.

Room Reverbs: Small Spaces and Atmospheric Detail

Room reverbs are my go-to when I want to create small, specific environments.

For example:

- Making a guitar feel like it was recorded in a small, smoke-filled club

- Adding intimacy rather than grandeur

- Enhancing realism without obvious reverb tails

Rooms are about impression, not exaggeration. They work best when you want the listener to feel a space rather than consciously hear it.

In a dense mix—especially when other instruments were recorded in real rooms—a subtle room reverb can help a part claim its place without drawing attention to itself.

Nonlinear Reverbs: Controlled Energy and Underused Potential

Nonlinear reverbs aren’t really a category in the traditional sense. Essentially, they’re created by taking a reverb and gating it so it ends quickly.

Despite how simple that sounds, nonlinear reverbs have some incredibly underutilized properties.

What makes nonlinear reverbs useful

- Strong sense of space without long decay

- Minimal masking of transients

- Excellent rhythmic clarity

- Controlled impact on drums and vocals

On a snare, nonlinear reverb adds size and excitement without washing out the groove. On vocals—especially rhythmically driven ones—it can provide ambience without affecting intelligibility.

This makes nonlinear reverbs a powerful alternative when traditional reverbs feel like too much.

Contextual Choices: Reverb in Real Mix Scenarios

When choosing reverbs, context matters more than categories.

For example:

- An acoustic guitar might need reverb not just for harmony, but for its rhythmic role in the mix.

- A lead guitar recorded in a room may only need the lightest touch—or a spring instead of a room.

- A vocal might sound better with a plate than a hall simply because it reaches density faster.

Sometimes a choice just feels right. When switching from a room reverb to a spring on a lead guitar, the difference can be immediate—clearer, more exciting, more alive.

That’s the one.

Reverb as Decision-Making, Not Rules

All of these categories—springs, plates, halls, chambers, rooms, and nonlinear reverbs—are simply guidelines. There are no laws, no fixed rules, and no single correct choice.

They’re just a way of thinking through the question:

What does this sound need right now?

Understanding why a certain reverb works in a given situation makes the decision faster, clearer, and more intentional—without boxing you into rigid techniques or expectations.